Swiss Cheese and Patient Safety

Dr. Sarrah is having a busy day. She passes her medical assistant (MA) in the hall and asks her to give a patient in room five an injection of a certain medicine. The MA may not have heard clearly and not gotten the right medicine, or the physician might have been thinking about a different patient in another room.

A patient was sent home from the hospital with instructions on how to care for a wound. The hospital provider did not realize the patient spoke English as a second language and did not fully understand the instructions. The care was not done correctly, and three days later, the patient came back in with a wound infection.

A patient is in the hospital with an infection to get antibiotics. They needed to go to the restroom, and instead of calling the nurse assistant for help, they tried to walk themselves. They get tangled up in the IV tubing, lose their balance, and fall, sustaining an injury.

According to the World Health Organization, people have about a one-in-300 chance of being harmed during health care (versus one in a million traveling by plane). Examples of patient harm include dispensing the wrong medication, failing to recognize worrisome symptoms, and others. While the risks in the clinics do not usually rise to the level of hospital care, there is still a risk for bad outcomes (e.g., prescribing an antibiotic that a patient is allergic to). It has been estimated that 6% of admissions to hospitals are due to a medication error.

An error is the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve a goal.

An adverse event is an injury caused by medical management rather than the underlying condition of the patient. An adverse event attributable to error is a “preventable adverse event.”

Patient safety is “the absence of preventable harm to a patient and reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with health care to an acceptable minimum.”

Swiss Cheese?

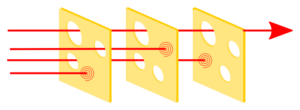

The Swiss cheese model of how accidents happen illustrates that, although many layers of defense lie between potential issues and accidents, there are flaws in each layer that, if aligned, can allow the accident to occur. In this diagram, the defenses stop three hazard vectors, but one passes through where the “holes” are lined up. Most of the mistakes that lead to harm do not occur because of the practices of one or a group of health care workers but are somewhat due to system or process failures that lead these workers to make mistakes.

A good example of the Swiss cheese model is how you might catch COVID-19. One layer might be a lack of physical distancing, another not doing good hand washing, maybe not using a mask when someone is sick, and not getting a vaccine. Maybe no single factor led to being infected, but if all the holes lined up, you did catch the illness.

So possible issues (or layers) which we see in health care include:

- Slips – intending to do something but did something else by mistake. An example might be classifying patients as urgent when they should be emergent.

- Lapse – an example might be forgetting to check an ID.

- Mistake – following an out-of-date protocol.

- Organizational – not ensuring enough staffing to do the work.

- Patient factors, technology factors, external/resource factors, and others

The Swiss cheese model can be simplistic, but it’s also very useful in communicating how failures can occur and in analyzing them, but only as long as we understand its limitations. If you are a reader of complex adaptive systems, you know the layers of the cheese may interact with each other and have an impact.

Prevention of Harm to Patients

The Institute of Medicine has emphasized the health care system to:

- Prevent errors by establishing protocols and following them.

- Learn from the errors that occur – this means constantly focusing on mistakes and near-misses.

- Build a safety culture involving health professionals, organizations, and patients. This means listening to all the voices involved in the patient’s care and saying, “See something, say something.”

Surgical Time-out as an Example

The discipline of surgery has incorporated many learnings from the patient safety movement. As noted above, they use a “time-out.” This will also often include the team members introducing themselves to each other to promote team spirit during the operation. The World Health Organization has shown that this process reduces surgical complications and mortality by more than 30%.

Sources

aafp.org/pubs/fpm/issues/2023/0300/patient-safety.html

sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S174391911930158X

psychsafety.co.uk/the-swiss-cheese-model/

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225187/

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swiss_cheese_model

jems.com/commentary/if-you-want-to-hold-the-errors-hold-the-swiss/